Probably not. But out of the ones I’ve heard, I’ve enjoyed these the most.

Listen to the Spotify playlist

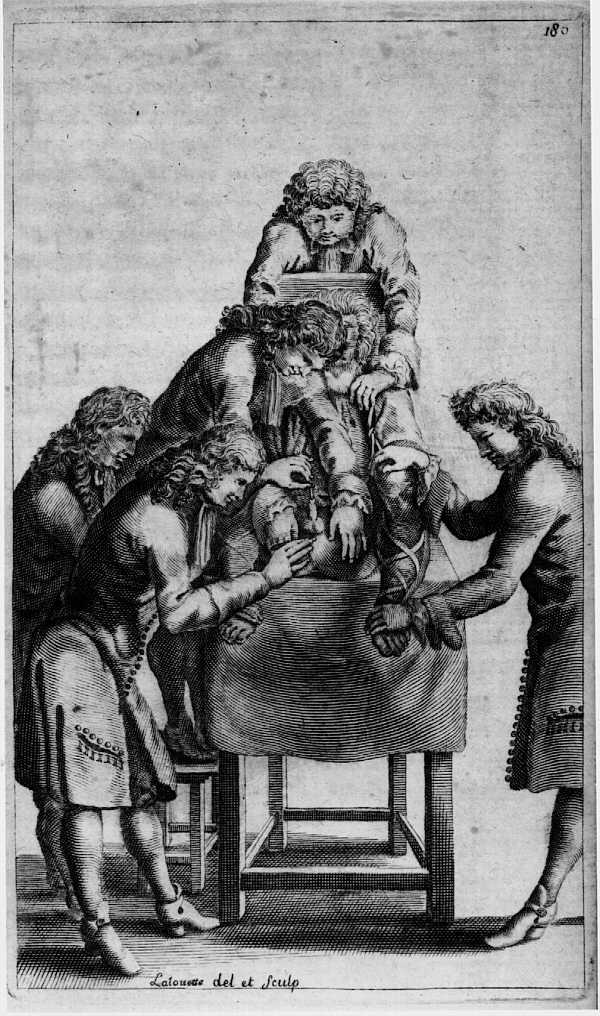

10. Le tableau de l’opération de la taille (Marin Marais)

Featured on: Marin Marais: Folies d’Espagne, La Rêveuse & other works (Jean-Guihen Queyras & Alexandre Tharaud)

Admittedly, this first entry is something of a ‘novelty song.’ It’s included on a record that has a lot more beauty to offer. Jean-Guihen Queyras & Alexandre Tharaud interpret viola da gamba pieces by Marin Marais (1656 – 1728) for cello and piano, with stunning results. You should check it out in full.

On this track, actor Guillaume Gallienne joins them to recite the text that Marais added to his piece Le tableau de l’opération de la taille. ‘La taille’ is the removal of a bladder stone, a horror Marais himself had to undergo when he was about 64.

Marais decided to pour his painful experience into a song. Much like Taylor Swift in Death by a Thousand Cuts, but with actual pain.

The text details the procedure. If you don’t understand French, consider yourself lucky. The music expresses the feelings of the patient. At the crucial/most excruciating moment, Marais decides the traditional Baroque style cannot capture the mood and skips ahead to early-twentieth-century expressionism. Who can blame him?

9. We played some open chords and rejoiced, for the earth had circled the sun yet another year (Dustin O’Halloran)

Featured on: Echoes (Orchestra of the Swan)

Midlifers like me remember the concept of ‘mix tapes’: a carefully selected collection of songs that fit on a 60-or 90-minute cassette tape. The idea was that such a highly personal selection would reveal to the recipient, usually a love interest, how sophisticated we were – without the hassle of actually having to express a feeling or a thought. Unsurprisingly, that never worked. Not once.

Orchestra of the Swan uses the mix tape concept to present a range of compositions that have no apparent reason to be on the same record: from Bach and Glass to Portishead and The Velvet Underground. If there’s an overarching message in all this, I couldn’t find it. It’s just a varied, enjoyable listen; sometimes, that’s all you want.

The track that stands out most is this minimalist piece, originally by the ambient duo A Winged Victory for the Sullen. The backbone of the composition consists, true to the title, of only a few open chords. They’re surrounded by flutters in the violins and some well-timed sighs of the cello.

Remove or add a few notes, and this would become the kind of music they generously disperse through your local wellness center. As it is, it sounds equally relaxing and moving. Halfway through, there’s a delightful Schubertian shift in the harmonies – always good for extra points in my book.

8. Fuga – allegro con spirito from piano sonata in e-flat minor, Op. 26, (Samuel Barber)

Nobody could accuse Samuel Barber of taking the easy road when he started his piano sonata. It’s a composition that summarizes at least two centuries of keyboard music, with nods to Bach, Beethoven, Schoenberg and Gershwin.

It’s all the more impressive that the piece presents a unified whole where the seams never show. This final movement combines a classical fugue with jazzy inflections, twelve-tone rows and some Debussy-esque orientalism – ending with a humorous twist that would have pleased Papa Haydn.

Speaking of whom:

7. Adagio from Symphony nr. 31 (Joseph Haydn)

Featured on: Haydn 2032, Vol. 13: Horn Signal (Il Giardiono Armonico – Giovanni Antonini)

Giovanni Antonini and Il Giardino Armonico got it into their heads to record all 106 Haydn symphonies by 2032. Each – beautifully packaged – volume presents a few works under some common theme. On volume 13, it’s the presence of a prominent section of no less than four horns.

This early adagio in a gently rocking siciliano rhythm is far removed from the monumental ‘London symphonies’ of the older master. Haydn wasn’t yet speaking to the world but trying to please his master by catering to the strengths of the members of his ensemble. Each gets his turn to shine, with a special role for the horns, of course. But the young(ish) ‘master of form’ already knows how to unite it all into one balanced and engaging whole.

6. Tarentelle, pour flûte, clarinette et orchestre, op. 6 (Camille Saint-Saëns)

Featured on: Bacchanale: Saint-Saëns et la Méditerranée (Zahia Ziouani)

Camille Saint-Saëns visited Algeria no less than eighteen times. There, he picked up some tunes to include in several ‘oriental’ compositions.

These days, such compositional curiosity could lead to accusations of cultural appropriation. And you can’t deny that in those heydays of French colonialism, the musical exchange didn’t exactly happen on equal terms. So it’s nice that on this record, Zahia Ziouani combines the orientalism of Saint-Saens with contemporary Arabic songs.

The track I’ve chosen is an airy tarantella – Italian rather than oriental and with some Viennese flavors in the middle part. The flute and clarinet tumble acrobatically over each other, with other instruments sporadically joining in. It’s an impressive demonstration of Saint-Saëns’ compositional skill and keen talent for orchestration.

5. Solstice In/Solstice Out (Anna Meredith)

Featured on: Nuc (Ligeti Quartet – Anna Meredith)

Two tracks for the price of one, because they’re as indivisible as yin and yang. Solstice In drives up your blood pressure through a string quartet that moves from agitated glissandi to dull and obsessive pizzicati, combined with a piercing trumpet. Solstice Out brings you down again when both strings and trumpet are muffled and hesitant. It’s kind of like a musical hot-and-cold bath to both jolt and soothe your nerves.

4. Dans mon jardin à l’ombre (Anonymous)

Featured on: Mon amant de Saint-Jean (Stéphanie d’Oustrac – Le Poème Harmonique)

In 2023, I raved about an album by Joel Fredriksen that artfully combines Leonard Cohen’s songs with Renaissance chansons. One of those songs could have easily made this list. But I decided to include something from another album with a similar approach. It serves a fricassee of 17th-century popular songs, 17th-century Italian opera, and 20th-century popular songs – though never within the same tracks.

Thanks to a distinctive accordion and d’Oustrac’s impressive and theatrical delivery, this album sounds so French that it should come with a complimentary baguette. This track is a dark tale about a woman turning down a handsome young soldier because she’s married to a jealous, even violent older man. Musically, it would pair remarkably well with Cohen’s The Partisan.

3. Ah ch’infelice sempre (Antonio Vivaldi)

Featured on: Sacroprofano (Tim Mead – Arcangelo – Jonathan Cohen)

There are still those who look down on Vivaldi because he was ‘formulaic.’ They’re wrong for two reasons. First, every Baroque composer was formulaic by later standards. Yes, even J.S. Bach. Two, listen to an aria like this one and tell me with a straight face that this would be out of place in the St Matthew Passion.

The lyrics would have to be adapted, as this aria recounts the peculiarly frustrating sensation of being rejected by a nymph. Much like Cold As You by Taylor Swift, but with a minor divinity from antiquity instead of an emotionally unavailable dude from the Nillies.

Plucked strings express the falling tears in the A and A’ sections. The ending of the contrasting B section is lovely: one note hangs like an unfinished thought when the A’ section unexpectedly kicks in. It demonstrates that no formula is ever exhausted in the hands of a genius.

2. Ich will schweigen (Johann Hermann Schein)

Featured on: Ein Deutsches Barockrequiem (Vox Luminis – Lionel Meunier)

In 2023, the wealthiest man in the world conclusively revealed himself to be a narcissistic and delusional cartoon villain. As if that fact wasn’t scary enough, a surprising number of people are happy to condone his behavior because he’s a genius – just like Beethoven, J.S. Bach and Taylor Swift. ‘Genius’ is a label that we apply very quickly. I did it three sentences ago. And it’s not without its risks, like inflating the contribution of a few while underestimating those of the many.

Although Johann Hermann Schein is dutifully mentioned in all books on baroque music, no one would ever call him a genius.

And yet, he composed what I consider to be one of the greatest masterpieces of the era. At least since I first heard it two years ago. It’s now recorded by my favorite baroque ensemble and, thus, an immediate certainty for this list. The text is a typical example of the long-lost virtue of humility, even slipping into the less commendable self-humiliation before the eyes of the Lord.

It ends with the sentence, ‘Ach wie gar nichts sind doch alle Menschen!’ – Oh, how all people are really nothing. Schein’s triumphant setting is paradoxical but fitting. Because what thought could be more liberating, both in the 17th century and today?

1. Maestoso from piano concerto nr. 1 in d minor (Johannes Brahms)

Featured on: Brahms: Piano Concertos (Simon Trpčeski – Cristian Măcelaru – WDR Sinfonieorchester)

I earlier outed myself as middle-aged. Though that has been mathematically correct for quite some years, I’ve only truly felt it in 2023.

One of the great things about growing older is that you’re less likely to be taken on a rollercoaster by your emotions. But it unfortunately also means that music doesn’t ‘come in’ as powerfully as it used to.

Gone are the days when I could put on Beethoven’s Seventh or Schubert’s Unfinished at any time of the day and immediately enjoy the feeling of having access to all the sorrow and joy entangled with human existence. These days, I’m just as likely to mellow out to a Haydn adagio. Nice, but not quite the same.

But I’m also not that old yet. And I particularly feel that when I’m exploring the works of the young Johannes Brahms. His first piano concerto was finished shortly after the suicide of Robert Schumann – his friend, mentor, and husband of the love of his life. They say the opening chords picture that fateful leap into the Rhine. It doesn’t get much more adolescently pathetic than that. And I mean that in the best possible sense.

The concerto is not virtuosic but challenging to play, which is the exact opposite of what you would want as a soloist. The orchestration is also not particularly brilliant, as Brahms was still refining that part of his craft. Its first performances were not well received. Today, it’s respected, of course, but not nearly as popular as, say, Beethoven’s 3-4-5, Tsjaikovsky 1, or Rachmaninov 2.

None of that matters when you listen to this fantastic recording. The chemistry between the soloist and orchestra is out of this world, as is the sound quality. It never failed to entrance me, remind me what got me into classical music in the first place, and even make me feel twenty again!

And if you’ll now excuse me, I must get New Year’s dinner going. I won’t sleep a wink if I eat after 8 p.m.