As every classical music lover must do at least once in their life, I’m attending Wagner’s complete Ring over two years. Because one does not simply walk into a world of gods, giants, dwarfs, dragons, and incestuous relationships, I’ll do my homework before every installment – and share it here. Part 3: Siegfried.

Another 17 years have passed since the events depicted in Die Walküre. Giant-turned-dragon Fafner sits contently on the gold that was stolen in Das Rheingold. But in the same forest, not too far from his cave, there grows a menace to his carefree existence.

That menace is Siegfried, son of Siegmund and Sieglinde, grandson of Wotan and Erda, and one of the most unlikeable people to ever set foot on an operatic stage.

The first action hero

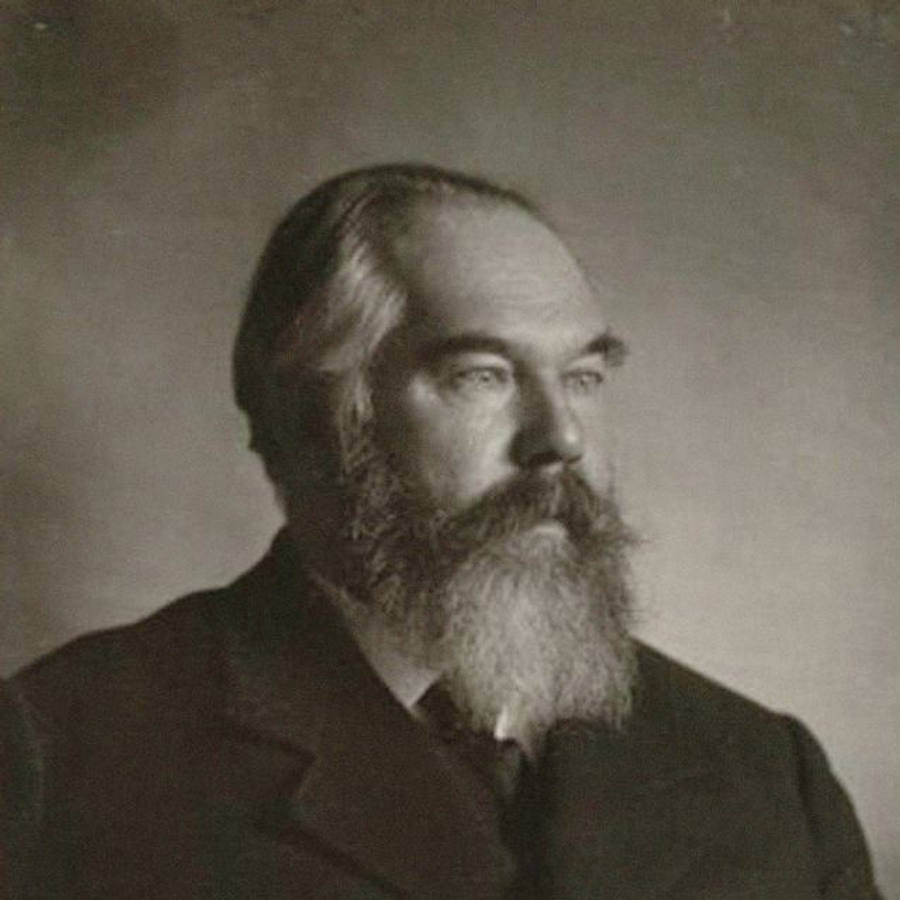

That Siegfried is such a disappointing character is not a minor defect. After all, Wagner’s Ring project started as a single opera named Siegfried’s Tod, which later became Götterdämmerung. The other three instalments were tacked on because Wagner felt Siegfried’s backstory could use some fleshing out.

Siegfried was, therefore, supposed to be the main hero of the Ring. In Wagner’s imagination, he is the “man of the future”, “the most perfect human being”.

He wasn’t only referring to Siegfried’s personality. Wagner described him as:

“a beautiful young man, in the shapeliest freshness of his power, the real naked man in whom I was able to discern every throbbing of his pulse, every twitch of his powerful muscles.”

Unsurprisingly, Siegfried was something of an icon for the fin-the-siècle gay scene, of which, fittingly, Wagner’s son Siegfried was a closeted member.

The problem is that people with such a level of perfection are inevitably boring. Why should we care about the ‘heroic’ deeds of a guy who’s not only borderline invincible but also knows no fear? Without fear, there’s also no bravery. Siegfried just goes around killing foes and dragons left and right without a second thought – like a less entertaining Chuck Norris.

But before you think Siegfried is no more than a cardboard action hero, let me assure you that his personality also harbors a dark undercurrent.

Siegfried and Mime

The opera’s first act is set in the workshop of Mime, the brother of Alberich, whom we met a mere seven hours ago. Mime has taken up the role of single father since Siegfried’s birth. His plan is to use the strong and fearless Siegfried as his tool to kill Fafner and steal the gold.

Siegfried, however, isn’t aware of this plan, which makes his behavior towards Mime rather troubling. He’s constantly belittling him and even brings a live bear into the house just to sadistically scare his pants off.

You kind of agree with Mime expecting more gratitude from his adoptive son.

It gets worse when you consider the reason for Siegfried’s vileness. He’s not rebelling because of Mime’s actions, his thoughts, or even his character. At this point in the story, he’s unaware of all of that. He simply despises the dwarf for how he looks.

It’s when Siegfried first admires the reflection of his own ripped body, strong jawline, blond curls and baby-blue eyes in a forest pond, that he first realizes he cannot be Mime’s real son. Mime is small, ugly, and talks with a high-pitched whiny voice. He’s also constantly busy making dinner and doing laundry, instead of doing manly stuff like catching bears.

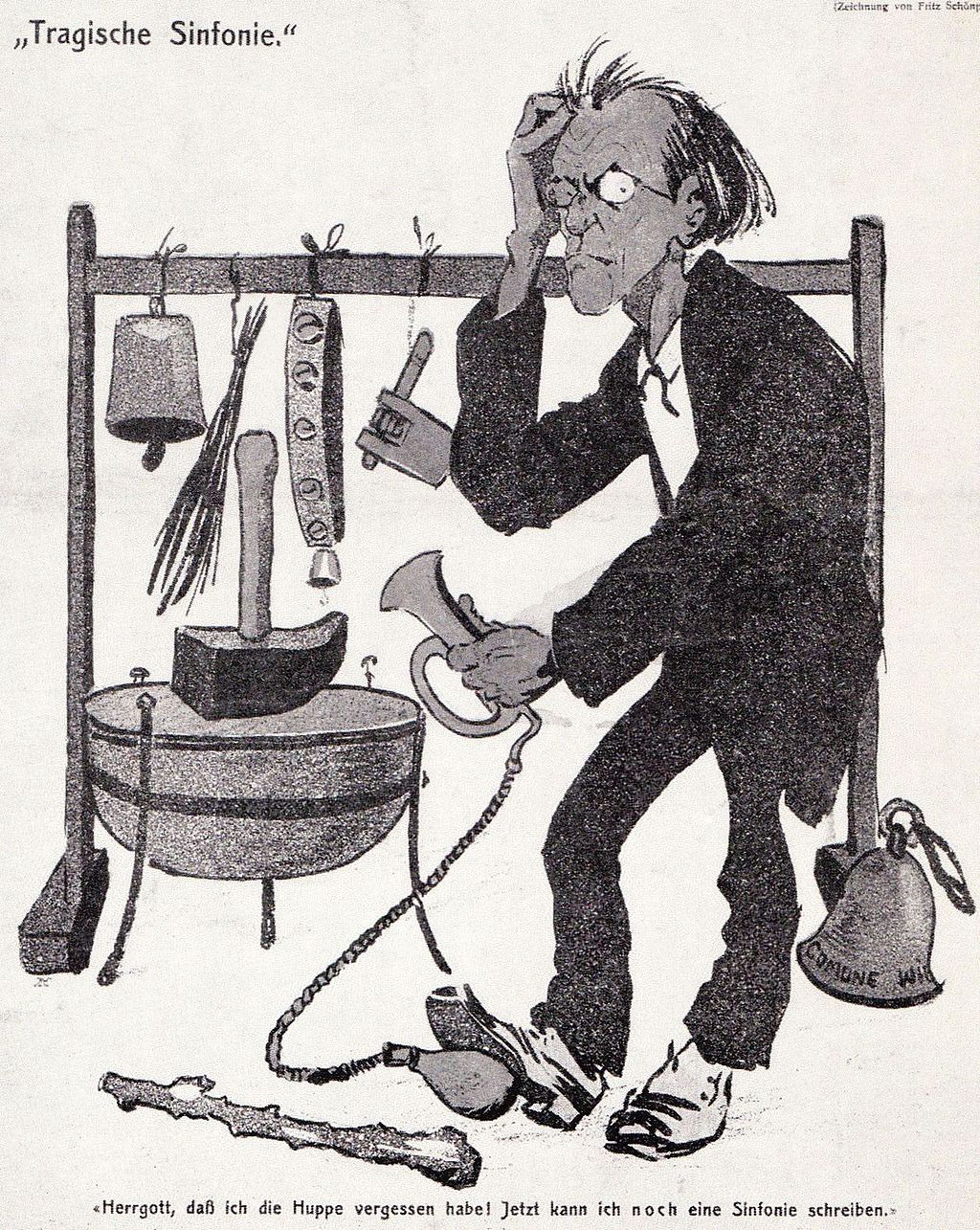

For Wagner, Siegfried’s hate for this effeminate and ugly dwarf is natural and just; it needs no further justification. It’s the dramatization of a racist worldview that’s as unambiguous now as it was then. In the words of Gustav Mahler: “I know only one Mime, and that is me!”

Mime and Wotan

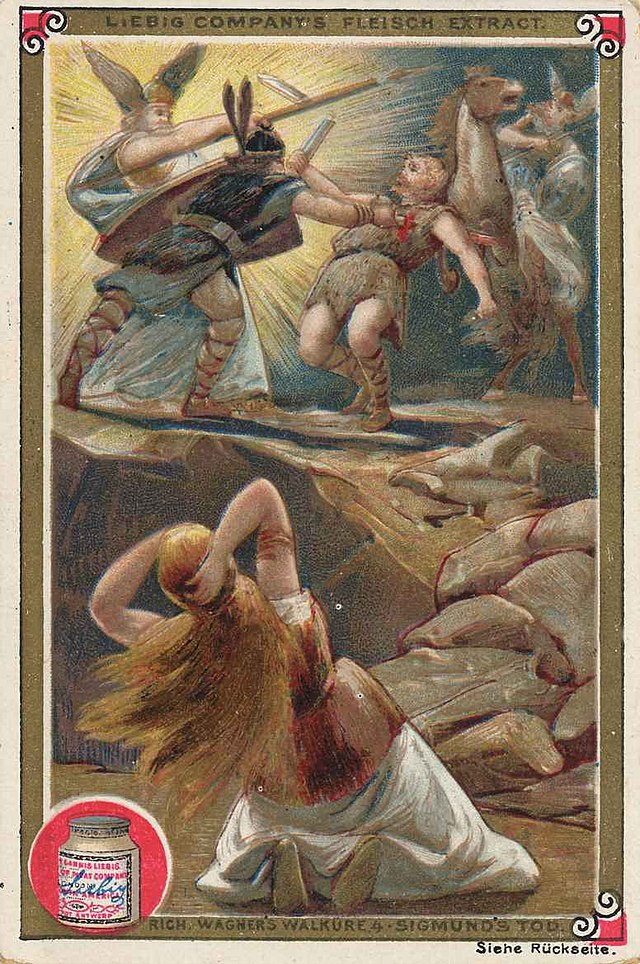

We immediately witness what a loser Mime is at the beginning of Act 1. Accompanied by the hammering Nibelungen music we remember fondly from Das Rheingold, he’s trying to forge a sword strong enough to butcher Fafner with. But Siegfried effortlessly breaks it in two.

Siegfried forces Mime to tell him who his real parents are. After he tells the story of Siegmund and Sieglinde, Mime shows Siegfried the pieces of Siegmund’s sword Nothung. Siegfried orders Mime to reforge it. Mime fails again; Siegfried leaves angrily.

Another old acquaintance enters, cleverly disguised’ as an old wanderer.

Wanderer Wotan asks Mime for some hospitality. After Mime refuses, he challenges the dwarf to play a game. He’s allowed to ask three questions. If Wotan is unable to answer them, the god will promptly lose his head.

These pitiful questions are all Mime can come up with:

- What race lives beneath the ground?

- What race lives on the earth?

- What race lives in the skies?

With a resounding ‘duh’, Wotan answers each question correctly: the dwarves, the giants, and the gods. He then turns the tables and demands that Mime answers three questions correctly or face death. Despite having nothing to gain and everything to lose, Mime agrees with the wager.

Wotan’s questions, however, are slightly more challenging:

- What race does Wotan love most but nonetheless treat very unfairly?

- Which sword can destroy Fafner?

- Who can repair that sword?

Mime knows the answer to questions one and two: the Wälsungs and Nothung. But he draws a blank on question three. Wotan reveals that Nothung can only be reforged by someone who knows no fear and – spoiler alert! – he leaves it up to that person to take Mime’s head.

Swordforger

Having received the news about his upcoming decapitation, Mime is understandably upset. But when Siegfried returns, he sees a simple way to escape his fate. Obviously, Siegfried is the fearless hero destined to kill him. So just teach him fear, and problem solved.

What better way to teach Siegfried how to fear than to introduce him to Fafner? As a bonus, he can steal the gold while he’s there and give it to Mime. Brilliant!

Although you might say this whole detour has been stupid because that was Mime’s plan for the last 17 years anyway. And you would be completely right.

The first act ends with Siegfried successfully reforging Nothung. Meanwhile, Mime brews a drink to poison Siegfried once Fafner is killed.

This so-called ‘forging song’ is the first musical high point of the opera. While the orchestra evocates the quivering flames and the rhythms of the anvil and the bellow, and Mime schemes in the background, Siegfried goes in all-out hero mode with relatively simple, repetitive melodies with a lot of leaps to showcase his boundless energy.

Not for the first or last time during the Ring, the music lends credibility to the story’s dubious claims. Here, Siegfried transforms into a hero before our eyes and ears, not through his actions or words, but through the musical magic wand that God somehow allowed Richard Wagner to wield.

Dragonslayer

Who’s that whining in front of the entrance to Fafner’s cave at the beginning of the second act? It’s Alberich the evil dwarf, Mime’s brother, and the original thief of the rhinegold. He’s waiting for the dragon to perish so he can take back the ring.

He’s joined by Wanderer Wotan, for no better reason than to tease his arch enemy a bit. He tells Alberich he’s not there to steal the gold, just to witness the events to come: not Wotan, but his own brother Mime will be Alberich’s contender for the gold. In typical Wagnerian fashion, he comes to warn the dwarf, then leaves the stage with a ‘que sera sera’ – events will unfold no matter what.

On the next daybreak, Siegfried and Mime arrive at Fafner’s lair. Mime wishes Siegfried good luck. Siegfried tells Mime to get lost. Then, our hero lays himself under a tree to wait until the dragon comes out for a drink.

We now encounter another aspect of Siegfried as the ideal romantic man: his close connection to nature. While the orchestra conjures up a tapestry of babbling brooks and rustling leaves – known as the Forest Murmurs – Siegfried tries to communicate with birds by blowing on a reed, although ultimately failing.

He immediately speaks Fafner’s language, though. When the dragon comes out of his lair, the two engage in a minimum of conversation (“I’m going to eat you.” – “No, you’re not.”) before their fight. Unsurprisingly, Siegfried effortlessly slays his foe with a stab through the heart.

Fafner is surprised and impressed by this “boy’s” courage and strength. With his dying breath, he gives a final warning: “Whoever blindly put you up to this, is also plotting your own death.” Is he talking about Mime, or is it possible that this key moment in the tetralogy holds a deeper meaning? Could the “blindly” refer to a one-eyed friend who foolishly created Siegfried to fulfill his own selfish desires?

Dwarfslayer

Although killing a dragon always looks nice on a pseudo-medieval résumé, it brought Siegfried no closer to understanding fear. He’s about to learn something else though. Some of Fafner’s blood has landed on Siegfried’s finger. When he licks it off, he’s suddenly able to understand the language of birds. One of them urges him to enter the cave where he will find the gold of the Nibelungen. However, the Tarnhelm will prove far more useful, and the ring would make him lord of the world.

When Siegfried goes into the cave, Mime reappears. He’s immediately joined by his brother Alberich, and they start a kind of rap battle about who’s more entitled to ‘rightfully steal’ the treasure.

As Siegfried reappears with the tarnhelm and the ring, the two dwarfs immediately flee and hide. The bird warns Siegfried that Mime wants to kill him. Luckily, the same dragon blood magic that enables Siegfried to understand birds will also allow him to hear the true meaning behind Mime’s treacherous talk.

Just like the previous encounter of Alberich and Mime, the next dialogue between Mime and Siegfried is an example of great musical comedy. While the music expresses the dwarf’s groveling tone, the words betray his murderous intentions. It’s a mismatch that will certainly put a smile on your face, as long as you don’t think too hard about how Wagner’s depiction of a two-faced dwarf rhymes with his views on certain members of the human race.

Siegfried, in any case, doesn’t appreciate the joke much. He kills Mime as foretold by Wotan, and buries him in Fafner’s cave, both forever united with their precious gold.

This afternoon of double murder leaves Siegfried anything but content. He still hasn’t learned fear and is now totally alone in this world. Luckily, his feathered friend knows the solution: a beautiful woman sleeping on a rock, encircled by flames and waiting to be woken by a hero who knows no fear.

Spearshatterer

The third act of Siegfried starts with two scenes of the kind that are seriously testing my patience as the Ring goes into its final hours. First, Wotan wakes up earth-goddess Erda to ask him how “the cruel wheel of fate can be stopped.” Apparently, he means the end of the Gods, but it’s not clear where he got that idea from. Erda tells him destiny is fixed, something that Wotan reproaches her for (although he said this himself to Alberich barely thirty minutes ago).

He then says that, because Siegfried knows fear nor envy, Alberich’s curse has no power over him and he will, with Brünnhilde by his side, redeem the world, even though this will entail the downfall of the gods. As was Wotan’s plan all along.

Nevertheless, when Siegfried shows up in the next scene, Wotan tries to stop him. First, with a barrage of inane questions: where are you going, where do you come from, nice sword – made that yourself? Then, when Siegfried gets understandably annoyed, he tries to block the road by holding up his fabled staff which Siegfried splits in two.

Again, while this scene logically makes no sense (at least not to me, but libraries of books disagree), dramatically it’s another high point. It symbolizes the new order obliterating the old and plays out the universal concept of generational conflict. Wotan’s solemn musical motifs, by now well-known to the listener, are ironically subverted by the young upstart Siegfried. Then the tension rises, and the actual spear-shattering comes with amusing thunder and lightning. Nothing now stops Siegfried from claiming his female companion.

Siegfried and Brünnhilde

Nothing to stop Siegfried except a ring of fire, that is. But as you would expect by now, he effortlessly walks through that. When he reaches the top of the mountain, he notices a person sleeping in full body armor.

He first removes the helmet and sees a man with beautiful long hair. It’s only when he also cuts away the breastplate that he finds out it’s a woman – the first one he ever lays his eyes on. Apparently, Mime didn’t neglect the sexual education of the boy in his care.

Finally, here’s a creature that Siegfried is genuinely afraid of. To be more precise, he panics because of the feelings she stirs up inside him. He calls out to his mother, which gives the whole thing a creepy Freudian touch.

Assembling his courage, Siegfried kisses Brünnhilde from her sleep. They immediately start to profess their love at first sight, both elaborately praising Siegfried’s mother – which should be a red flag on a first date.

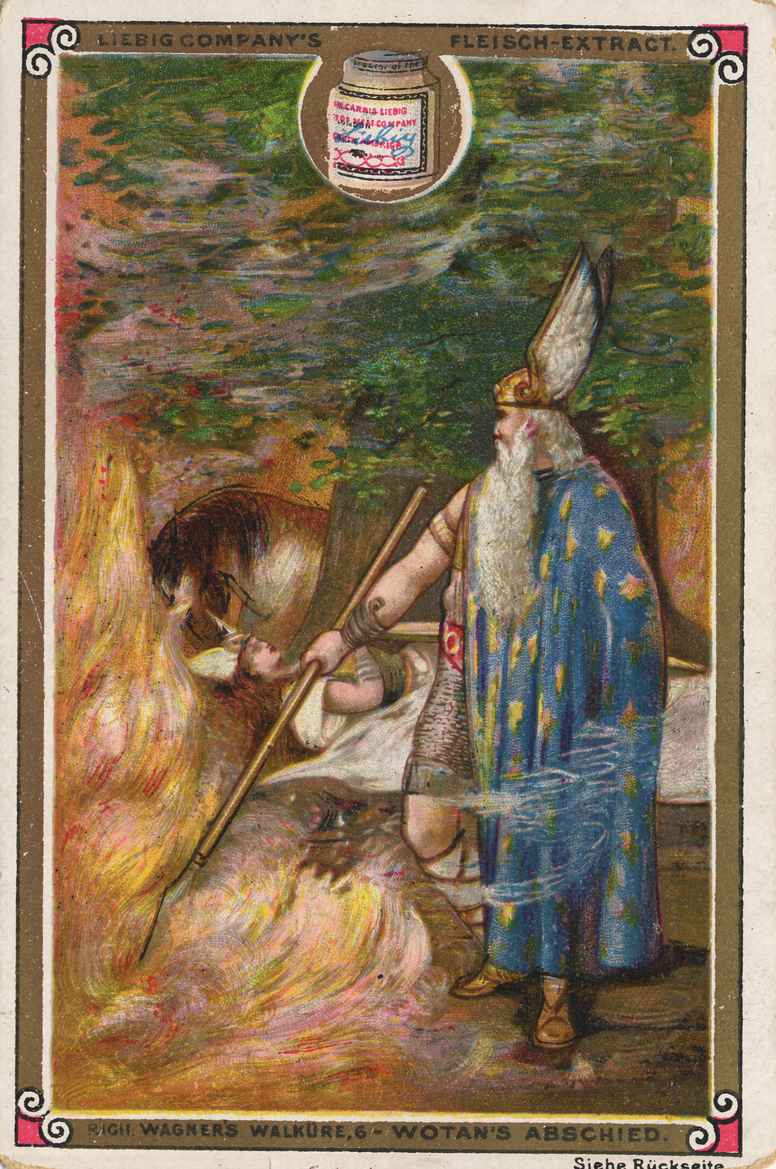

However, while Siegfried is getting hornier by the minute, Brünnhilde is starting to have second thoughts. Because of Wotan’s punishment in Die Walküre, she’s now a mere, and virginal, mortal. Her armor is now literally taken away, leaving no defense against desires that rage both in Siegfried and herself.

It’s hard to miss the sexual subtext of this scene. This is, after all, written by the composer who had just finished Tristan and Isolde. But the final musical highlight of this opera is something that comes very close to a traditional aria that could have featured in The flying Dutchman. Brunnhilde pleads with Siegfried to leave her in peace and preserve her immaculate image in his memory:

However, the flames of love have already spread beyond control. With a generous portion of ecstatic vocalizing, Siegfried and Brünnhilde declare each other their undying love. The ring is in the hands of a couple that should be able to withstand its corrupting power.