Jean-Philippe Rameau and Claude Debussy were both French.

In my mind, that’s about the only thing they have in common. You’ll soon find out why.

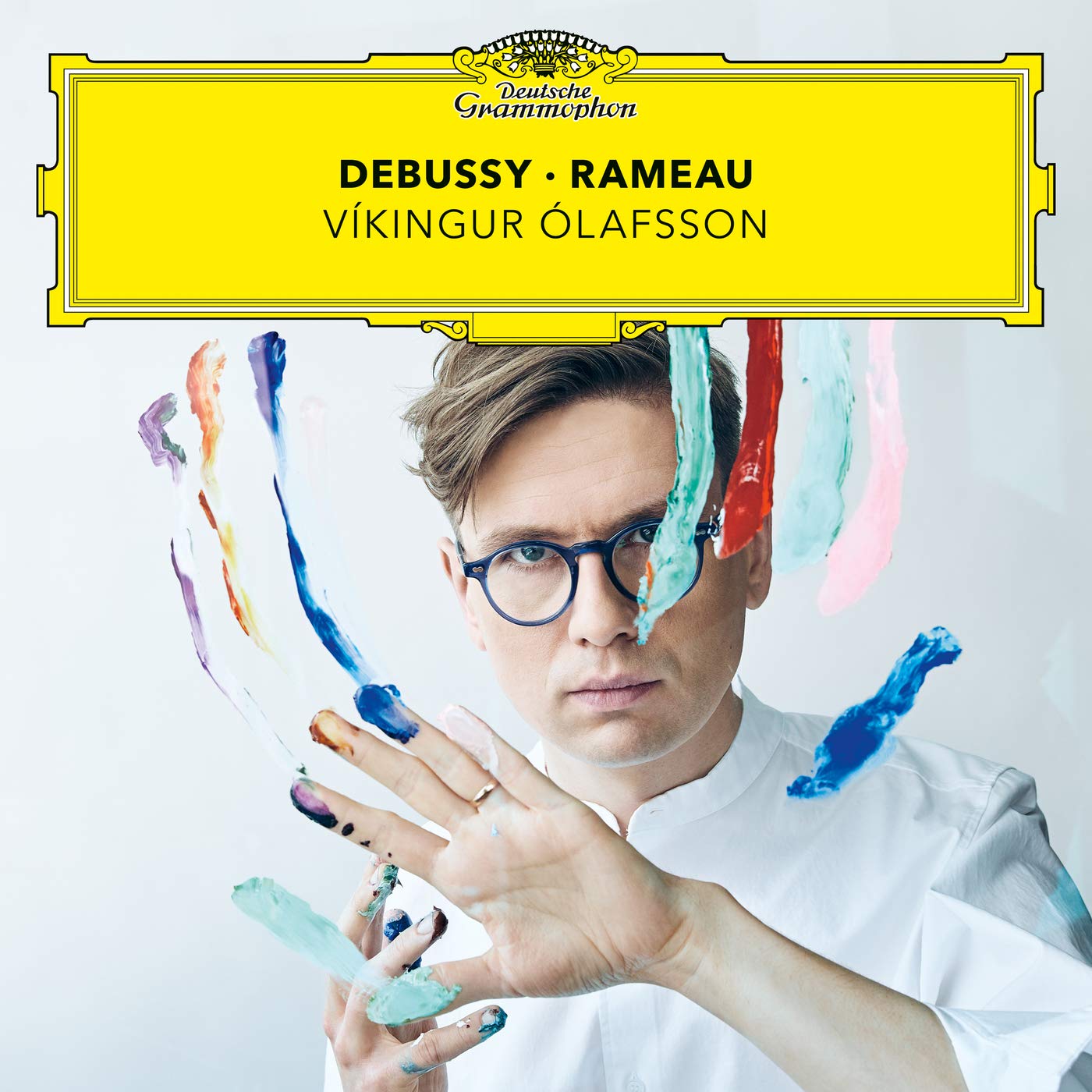

But in Víkingur Ólafsson’s mind, Rameau and Debussy have an intimate connection – despite the almost 200 years between them.

And Ólafsson is one of the hottest new piano virtuosos right now. So his opinion is worth a lot more than mine. Moreover, he enforced it by recording an album that illustrates that connection.

Apart from illustrating that you’re never too old to enjoy finger painting.

Ear-opener

Debussy – Rameau is not the most imaginatively named record of the year. You wouldn’t suspect that this is a ‘concept album’: Ólafsson carefully chose and arranged the tracks so the whole would be greater than the sum of the parts.

There’s an idea that he wants to convey:

“make [Rameau and Debussy] into musical friends and create a dialogue that might show Rameau in a futuristic light, and find Debussy’s deep roots in the French Baroque”

Does he succeed? Certainly, his interpretation of Rameau was an ear-opener to me.

Maybe it’s because I only knew his keyboard works from harpsichord performances.

Maybe because he literally wrote the rule book of tonal harmony.

Maybe because of the schoolmasterish air that exudes from his portraits.

The fact is I never realized how emotional and intense Rameau’s music can be.

Jolts of pleasure

This intensity of Rameau’s music is exactly what Ólafsson makes clear. Not by adding pathos or making grand gestures. But by charging the music with palpable tension.

From the very first note of every one of these little pieces, you get the feeling that there’s a massive amount of sadness, joy, melancholy, rage … bubbling beneath the surface.

Sometimes it makes a ripple in the neatly woven musical canvas: an ornamental figure drawing attention to itself, an accompanying melody in one of the middle voices making a bold statement.

Thanks to Ólafsson transparent and sensitive style, none of these details go unnoticed. And each one rewards the listener with a little jolt of pleasure.

I like it, is what I’m trying to say. And I understand how this ‘impressionistic’ Rameau would pair well with his compatriote from almost two centuries later.

Even if that’s a connection I don’t feel …

Moments of irritation

I can only assume that Ólafsson’s interpretation of Debussy is just as good. Because I’m convinced that the only thing a skilled pianist needs in order to give an adequate Debussy performance is a functioning sustain pedal.

You see, I’m not a big fan of Debussy’s piano music. To put it mildly. From his dull pentatonic melodies to his endless ‘dreamy’ scales up and down the keyboard – they irritate me to no end.

And in what universe is that an acceptable way to wear a hat?

Seriously.

There’s only one Debussy track on the album that doesn’t make reach for the skip button: Jardins sous la pluie is a lively piece in the style of a baroque toccata. It fits in perfectly with the Rameau pieces and makes me realize that Ólafsson’s concept works. Even if I can’t fully enjoy it.

Fortunately, on this album, there’s a lot more Rameau to enjoy than Debussy to be irritated by. And if you like them both, you will no doubt be swept away from the first note to the last.

Want to keep up with my classical musings? Enter your email address and click subscribe.

More about baroque music

- Acis and Galatea by Handel

- Was Handel gay?

- Handel and the Hanoverians

- My visit to the Handel & Hendrix museum

- Tartini’s Devil’s Trill