As every classical music lover must at least once in their life, I will attend Wagner’s complete Ring over the next two years. Because one does not simply walk into a world of gods, giants, dwarfs, dragons and incestuous relationships, I’ll do my homework before every installment – and share it here. Starting with: Das Rheingold.

Wagner’s collection of four operas, Der Ring des Nibelungen, is essentially the earliest example of the modern fantasy genre. Without it, there would probably be no Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, or Game of Thrones.

That reference to blockbuster movies and TV shows may help lessen the concerns of those about to embark on fifteen hours of German opera. But it also runs the risk of creating false expectations.

Disappointingly, the Ring doesn’t contain massive assaults on medieval strongholds or titillating whorehouse scenes.

There may be some impressive stagecraft involved. And the music can be as deliciously pompous as the best Hollywood has to offer. But most of the time, you’ll be watching a handful of people elaborately singing about their convoluted feelings.

Are you worried again? The good news is that you can gently roll into it all with Das Rheingold, the opera that packs the most action of the four Ring installments, in the tiny duration of two and a half hours. However, be aware that there probably won’t be an interval, as there are no breaks in the music between the four scenes.

An accessible appetizer to the Ring’s main courses

Das Rheingold is also the Ring opera that’s easiest to understand. In its entirety, Der Ring des Nibelungen is an incoherent mess. Nietzsche speculated that Wagner deliberately obfuscated the story because he feared it was too simplistic. There is, however, a less malicious explanation for the Ring’s maddening inconsistencies. From the time Wagner wrote the original story until the moment he composed its last note, more than twenty-five years had passed. Twenty-five years in which Wagner transformed from an arrogant, antisemitic left-wing revolutionary/terrorist to an arrogant, antisemitic right-wing bootlicker of Europe’s craziest monarch. Naturally, the big messages he wanted to convey with his operas had also changed.

Das Rheingold, composed in 1854, stays true to the Ring’s original concept. In 1848 – when revolutions engulfed Europe – Wagner cobbled together his ‘myth’ from various Scandinavian, German and Greek source materials. It’s meant to be a story that presents universal human themes. And we’ll see that it sometimes resonates eerily with the world we know today. But in essence, it’s a commentary on 19th-century society, particularly its inequalities.

Characters in Das Rheingold

Gods

As a lot of people know, the Ring is about gods. Wing-helmed, blonde-haired, sword-wielding gods. And you might think, knowing what everybody knows about Wagner, that these divine heroes are personifications of German superiority.

In reality, Wagner’s gods are a sad bunch. They’re the supposed leaders of their world. But their power doesn’t come from their spiritual, intellectual, or moral superiority. Instead, they use violence to get their way. More importantly, they make social rules that they then break themselves. They’re hypocritical, vain and corrupt. For Wagner, they represented the contemporary ‘enlightened’ monarchs and clergy.

In Das Rheingold, only Wotan (the ruler of the Gods), his wife Fricka, the half-god Loge and the earth goddess Erda are important characters. The others merely hang around to demonstrate their pointlessness.

Dwarves

Like in Lord of the Rings, Wagner’s dwarves are driven by material lust. Their home is Nibelheim, where they delve for gold in the earth’s bowels and have little interest in anything else. They’re also quite hideous to look at. For Wagner, they probably represented the 19th-century bourgeoisie.

In Das Rheingold, we meet the dwarf brothers Alberich and Mime.

Giants

Giants are big and stupid. They’re also hard workers. For Wagner, they probably represented the proletariat, although nobody seems to know for sure.

In Das Rheingold, we meet the giant brothers Fafner and Fasolt.

Rhine maidens

The Rhine maidens are water-nymphs that swim, sing and protect the Rhine gold for which the opera is named. They’re beautiful and haughty, two facts that will propel the story to its disastrous conclusion.

The story of Das Rheingold

The original sin

The iconic opening of Das Rheingold is Wagner’s musical evocation of the beginning of the world. It starts not with a bang but a whisper: a steadily expanding E flat major chord.

We then meet the three Rhine maidens frolicking in the water. Suddenly, they notice Alberich ogling them. The dwarf tries to seduce them, but they mock him for his hideous appearance.

In his rising frustration, Alberich sees the gold the Rhine maidens are meant to guard. They tell him that anyone who wins the gold and makes a ring out of it will become master of the world. But he would have to ‘forswear the delights of love.’

What then happens is Wagner’s version of the downfall. Against all expectations, Alberich, the world’s first incel, renounces love in exchange for power. He steals the gold, leaving the Rhine maidens panicked and grieved.

In this first scene, Wagner, the dramatic genius, introduces the opposition that defines the entire Ring: love versus power.

The misguided contract

We now meet the gods high up a mountain. There, Wotan built a fabulous castle named Walhalla – an ostentatious symbol of his power. That’s to say, the giants did the actual building. And Wotan is only now pondering how to reward them for it. Being a god, he entertains the silly illusion that he’s above mundane stuff, such as money.

He’s so silly that he drafted a contract with the giants: in the event of a cash flow problem, he would fulfill the payment in kind by giving away his sister-in-law Freia. You could argue that can be a small price, but in any case, Wotan’s wife Fricka – Freia’s sister – isn’t too happy with this arrangement. Neither are her brothers Donner (god of thunder) and Froh (god of spring).

The gods’ attachment to Freia is not only emotional. Her golden apples also ensure their eternal youth. So, her disappearance would mean a certain death for everyone on that hill.

What was Wotan thinking?

The answer is that he took the advice of Loge, the (half-)god of fire who joined the Gods for opportunistic reasons. He’s the smart guy in the Ring, but that doesn’t mean he’s wise. In fact, his guidance will lead to the gods’ downfall.

Loge promised Wotan he would find a way out of his promise to the giants, but he’s now nowhere to be seen. Meanwhile, the giants have arrived, demanding that Wotan keeps his word. Notice that Wagner’s music to characterize the giants is as deliciously unrefined, even clownish, as Fasolt and Fafner themselves.

Just in time, Loge joins the scene. He tells everyone the story of Alberich stealing the gold from the Rhine maidens. Surely the gods should be willing to steal it back and return it to the rightful owners? Most Gods agree, also because they feel the upstart dwarf could become a challenger for the power that they consider their birthright.

Wotan isn’t so sure. After all, stealing from a thief is still stealing – against his precious rules. Until Fasolt and Fafner mention that the Nibelung’s gold would be a fitting reward for their labor. Wotan feels a sudden compassion for the Rhine maidens and decides to go with Loge to Nibelheim to retrieve the gold.

In capitalist hell

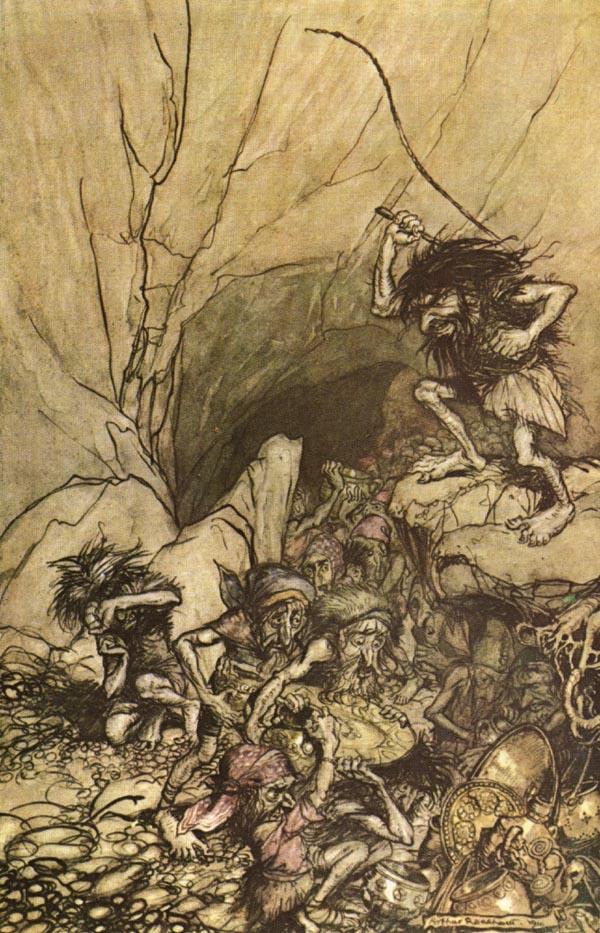

The descent to Nibelheim is one of those scenic and musical transformations that Wagner excels at. As we leave the stately atmosphere of Walhalla behind, we’re greeted with a restless motif in the strings of the orchestra and the sound of hammering on eighteen anvils. Yes, literally eighteen anvils:

This is Wagner’s unforgettable evocation of the horrors of the industrial revolution. Alberich has become an entrepreneur and turned his home into a capitalist dreamland.

His fellow dwarves, including his brother Mime, are forced to work for him 24/7. Just when we come in, he’s fitting the Tarnhelm, a piece of high-tech headgear that can transform him into any shape or make him invisible. The explicit purpose is to spy on his workforce without himself being seen. All pretty visionary stuff.

On meeting Wotan and Loge, Alberich boasts about his wealth and power. Soon, he will bend the world to his will, and the reign of the gods will be over. When the cunning Loge asks Alberich how he can prevent someone from stealing the ring, Alberich demonstrates the power of the Tarnhelm by transforming into a serpent.

Loge then asks Alberich if he can also turn into something tiny. What follows is comic book stuff. A moment later, Alberich is bound and dragged to the divine mountain top.

A curse and fratricide

Alberich comes up with a plan: give up his hoard of gold to the intruders but keep the ring, and then start again. But the plan fails. After the gold is transferred, Wotan demands that Alberich also give up the ring, forcefully taking it from him. Just before he is released, the dwarf curses the ring: all who have it will suffer, and all who don’t have it will want it.

It won’t take long before the curse starts to do its work. When Fasolt and Fafner arrive, they put the gold in a pile before Freia. Only when she’s entirely out of sight (Fasolt is genuinely in love with her) shall they be content.

Wouldn’t you know it, when all the gold is on the pile, exactly one ring-shaped whole remains through which one of Freia’s fair eyes can still be seen. The giants demand that Wotan give up the ring, which the god, already consumed by the ring’s power, refuses.

Then Erda, the earth goddess one step higher in the divine hierarchy than Wotan, shows up. She orders Wotan to give up the ring. But also casually mentions that the Gods will perish in any case, which is weird.

Anyway, Wotan decides to follow Erda’s advice. He hands the ring to the giants, who immediately start fighting over it. In a literal slapstick moment, Fafner kills Fasolt with his stick and walks away with the gold and the ring.

The gods decide the show’s over, and it’s time to settle into their mighty new fortress. Donner has his moment in the spotlights when he conjures up a thunderstorm, after which a rainbow bridge allows the gods to stride to Walhalla.

While the other gods seem to think their power is secured now the ring is in the hands of the stupid Fafner rather than the cunning Alberich, Wotan is not so sure. But how can he retrieve the Ring without breaking his own precious laws?

Around that central dilemma, the next twelve hours of opera will revolve.