In an earlier article, I mused about the many hours I’ve wasted watching music-related YouTube videos. This post is about the channel that stole the most of my time: Authentic Sound by Wim Winters – the closest thing the classical music universe has to a conspiracy theorist. At least if you believe some of the comments on his channel or on discussion boards such as these.

So, what vile beliefs does Winters peddle on his channel? That Mozart was the leader of a band of child molesters? That Schumann was murdered by Brahms so he could steal his wife? That Beethoven was black, or Handel was gay?

Prepare to be disappointed …

Wim Winters is the inventor and tireless evangelist of the whole-beat metronome practice or WBMP: he’s convinced that music from the 18th and 19th centuries should be played slower than it usually is. And I mean waaaaaay slower. This is what he thinks Beethoven’s fifth symphony should sound like:

To understand where that comes from, we need to talk about metronome marks.

The mystery of Beethoven’s metronome

The metronome was invented in Beethoven’s time. In fact, he was one of the first of many composers who enthusiastically embraced it. They jumped at the chance to ensure ‘faithful’ executions of their music. Just indicate the number of beats per minutes at the top of the score and that’s the tempo everyone should stick to. What could be simpler?

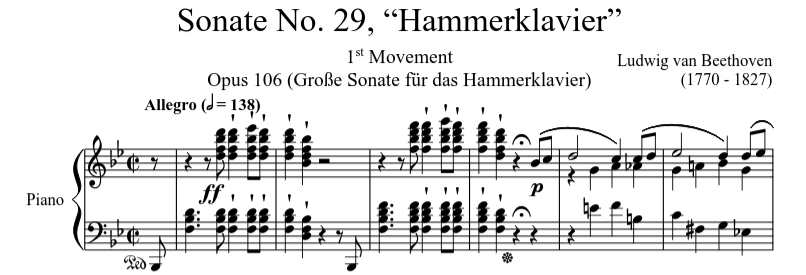

A lot, apparently. Because if we look at some of these metronome markings today, they seem unreasonably fast. In cases such as the marking Beethoven gave to his Hammerklavier sonata, it makes the music virtually unplayable.

It’s understandable that, for a long time, most performers pretended they didn’t see those metronome numbers and played the music considerably slower. That changed when the historically informed performance (HIP) movement picked up steam in the 1970s. True to their brand, the HIPsters dusted off those ‘authentic’ tempo indications and set out to prove they were not so absurd after all.

There’s a technical argument to back this up. Period instruments – such as baroque violins – make ‘shorter’ sounds that favor faster tempi. Pianofortes, moreover, have a lighter mechanical action than contemporary pianos, which makes them easier to play at high speeds.

And yet, that doesn’t conclusively solve the tempo problem. For one thing, the HIP performers, even if they play considerably faster, rarely reach the giga speeds that are proscribed for some works.

And it still seems strange that 19th century amateurs would have been expected to play at speeds that even present-day professionals struggle with. Consider that Chopin, who was not a show virtuoso like Liszt, would have been unable to play some of his own scores at the speeds he proscribed.

A very poor amateur pianist myself, I regularly play some of have J.S. Bach’s inventions – works that are explicitly meant for beginners. To play them at the metronome speeds mentioned in my score, is far beyond my reach. And even if I could pull it off, the result would sound ludicrous. The editor seems to be aware of this because they added a footnote:

“The metronomisations based on transition are intended for purposes of study, otherwise a more moderate time might be advisable throughout.”

Notwithstanding the abominable translation, it’s clear they think that the proscribed tempo would sound unmusical. So they advise you to slow down for actual performances. But what could be the point of making students play Bach at speeds that are not only unattainable, but also unmusical?

When I play those inventions, I regularly land at a tempo that’s about half as fast as the metronome mark. It’s feasible, and it sounds okay. And now we’re getting there …

From broken metronomes and stupid composers to the WBMP

Over the years, people have come up with several solutions to the metronome problem. A popular one is that there were a lot of broken metronomes around in the 19th century and that composers were too stupid to notice. A recent one even speculates (with the help of artificial intelligence no less!) that Beethoven wasn’t even smart enough to properly use a metronome.

More interesting is the idea of a psychological effect: music goes faster in the imagination than in reality, which compels composers to exaggerate their tempo indications. Perhaps, but that’s only valid if you assume that they never assess those spontaneous markings – at the keyboard for example.

And then there’s Wim Winters’ solution: whole-beat metronome practice (WBMP). In a nutshell: the first composers who encountered the metronome didn’t measure by the ticks of the mechanism but by the swing of the pendulum. As there are two ticks for every swing, their tempo indication needs to be doubled and the music would sound half as fast. Or double as slow.

Problems with the whole-beat metronome practice

Winters’ theory is certainly intriguing, and some of the examples he (cherry)picks certainly make you wonder. I recommend his series on the Bach inventions I mentioned earlier. Agree with him or not, but after that you cannot hold up the claim that there’s nothing fishy about 19th century metronome marks.

But there are also reasons for skepticism. For instance: wouldn’t you expect at least some, or even a lot of, direct historical evidence? Remember, Winters doesn’t only apply the WBMP to Beethoven and his pupils but also to composers like Chopin, Schubert, Schumann, … even all the way up to Max Reger. Why did no one, during those almost one hundred years, feel the need to express their amazement of the fact that the whole world had been using the metronome wrong?

Another reason to doubt the WMPB is the fact that if the music was played at a little less than half the speed, concerts would have taken almost twice as long. Haydn and Mozart symphonies would have easily gone on for more than 45 minutes – Beethoven symphonies regularly close to 80 minutes, the 9th even 2 hours. Unlikely, since contemporary critics complained about the outlandish length of some of Beethoven’s symphonies because they took more than 45 minutes. Although, it must be said that it’s very hard to determine what exactly was played during 19th-century concerts. Were all the movements of a symphony always performed? And what about the repeats within movements?

Finally, there’s the very obvious problem of some music in triple meters such as 3/8. Say that the metronome indication is 100/dotted quarter note, and you want to interpret it according to the WBMP. That means you would need to play mostly three notes against two ticks – or in constant polyrhythm with the metronome. It’s doable but far from comfortable. And it strengthens the first argument against WBMP: why did no one in the 19th century protest against such obvious (and easily avoidable) impracticalities?

And then, of course, there’s the cuckoo at the end of Beethoven 6th symphony.

The swinging of the pendulum

So, Winters’ WMPB theory is – though highly entertaining – very suspect. Nevertheless, he has a lot of committed believers. People who think that this is what Schubert’s Fantasy in f minor should sound like:

Crazy, right? But wait a minute: is it that much crazier than this interpretation of – again – Beethoven’s Hammerklaviersonate?

Impressive, sure. But to me, that tempo choice – though in the other direction – is almost as absurd. The difference is that the person making that choice is a highly respected pianist instead of a guy with a fringe YouTube channel. By the way, that’s still not as fast as Beethoven’s ‘single beat’ metronome mark. Here’s how that would sound.

When it comes to the speed of performed music before the recording era, we will always remain in the dark. What is certain, is that tempos have varied considerably over the years, owing to nothing more than fashion.

The HIP movement was fashion posing as science. Its anti-bourgeois, back-to-the-basics attitude paired well with the post-1960s cultural climate. Its love of speedy performances was partly a spill-over from pop and rock aesthetics. And it greatly benefited from the fact that recordings help to erase the lack of volume of period instruments. There’s nothing authentic about listening to a Beethoven symphony played by a supposedly 18th century orchestra and then turning it up to eleven.

And now, the pendulum is swinging back again. Look at the success of post-classical, neoclassical, indie classical or whatever you want to call it: slow, meditative music is all the rage. Wouldn’t it be perfectly natural if that influences the way we choose to interpret Beethoven or Chopin? We don’t need Winters’ creative historical research to back that up. But we certainly also don’t need the dogmas of the authenticity school to hold it back.

The revenge of the amateurs

It’s my hope that the relative success of Winters’ channel is an early indication of another swing of the pendulum: the death of classical music as a spectator sport. And the return of the amateur musician as the true hero of musical history.

The tagline of Winters’ channel used to be ‘They wrote music for you’. Whether that’s true of all music after Beethoven is another matter. But it’s certainly a fact that the success of the classical repertoire is mostly down to the incredible market for sheet music that existed during the 19th and early 20th century. Just about every middle-class house had a piano where the works of Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Chopin, … were saved from oblivion. And it’s safe to guess that wasn’t done with the technical mastery of today’s maestros who practice sixty hours a week.

Playing an instrument – alone or together – is a gloriously absorbing activity that lets you experience music in a totally different way from merely consuming it. And yet, many of us learn to play an instrument when we’re young, and then give it up when we realize that ‘competence’ is all we can strive for. We seem to believe there’s no greater embarrassment than to become an imperfect version of the standard that is the professional musician.

It should be the other way around. The amateur musician is the standard, and the flawless, breakneck-speed virtuosos served to us by the music industry are circus freaks. They’re by no means out of place in the concert hall, but live music making should not be limited to payable venues.

Saying goodbye to unattainable tempo expectations is one of the easiest ways of greatly expanding the repertoire for amateur musicians. It’s no wonder that they flock to Winters’ YouTube channel. Or as a person on this forum so eloquently puts it:

“They probably have the same problem as him: no technique but still wants to play.”

Exactly. And all the more power to them.

Want to keep up with my classical musings? Enter your email address and click subscribe.

you can insinuate others are idiots as much as you want. The fact remains that Winters is not an idiot or someone with a youtube channel, he is someone who started winning organ competitions after 2 years of playing, and no virtuosity is needed in musicology, which is what Winters does. You don’t like what he says? This is irrelevant to the fact that you have no counter arguments or facts that disprove what he says. Being a respected concert pianist has little to do with musicology…..you should learn the difference. And the word ‘amateur’ doesn’t mean one is an idiot and don’t understand virtuosity. Further: virtuosity has NEVER been a requirement in music, and adding more technique doesn’t necessarily makes music better. Virtuosity was even derided by many of the most eminent musicians. Lastly, learning to play a piano repertory really well or fast, don’t make of you a virtuoso. There’s no such a thing as a virtuoso today, in the past virtuosos could improvise, for example. The so called ‘virtuosos’ today can play their Chopin etudes fast, but can’t even improvise a decent arrangement of Happy Birthday. In this sense, they are therefore amateurs themselves.

LikeLike

prowannabee, even for me with my moderate level of knowledge, it is easy to find a numbe of counterarguments to Wim Winters’ claims. But I’m tired of my opponents not answering, but keeping silent. Later on I find the ones with the same erroneous WW’s arguments under other videos! It is cowardly and does not provide any clarifying answers. So if you really want to get to know some counterarguments, you have to promise me to answer!

LikeLike

by the way, I didn’t mean to say that a lack of virtuosity implies a work to be easy to play. That’s not what I meant at all. What I meant was that the word ‘virtuoso’ is used today far, far too easily….concert pianists today are just that, good (or in some cases great) concert pianist. Not VIRTUOSOS…..

LikeLike

One of the worst posts I´ve ever encountered. Nothing but hatred and rage in, no practical arguments and always an underlying arrogant writing style.

LikeLike

If Wim Winters is right, who does he sometimes have to censor and manipulate listeners?

LikeLike

Maarten makes some interesting comments that seem to support Wim Winters WB but then accuses him of playing slowly because he has no technique. Confusing! Putting aside WB many modern performances are too fast and performers simply ignore tempo markings, dynamics/expression marks etc. This problem begins in the music schools/academies and also our modern day obsession with competitions. How else do you kick-start your career other than blinding your audience with sheer virtuosity? Then again there is always sex and that too is being increasingly used to sell classical music to a wider audience. Wim Winter is not only a fine keyboard player but also someone who has done a great deal of research into WB and tempo reconstruction. Detractors are free to disagree with WW but we’re left with the original problem at the heart of this discussion, why are so many metronome markings impossibly fast and are we meant to believe that Beethoven e.g couldn’t use a metronome correctly?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the reaction, Robin. To be clear, I don’t for a moment doubt Wim Winters’ technique. But now that I reread it, I understand your confusion.

I don’t quote “They probably have the same problem as him: no technique but still wants to play.” because I agree with it. Rather, it’s an example of the wholly irrelevant accusation leveled at him and, more importantly, his ‘followers’.

Whether his theories are correct or not, if they empower amateur musicians to play repertoire that would otherwise intimidate them because of unattainable tempo expectations, that’s undoubtedly a good thing.

LikeLike

Thank you for clarifying your position. I recently heard a number of performances of Beethoven op 33 no 5, not one of them took any notice of Beethovens’ marking “ma non troppo” added to his Allegro. There is a case to be made that tempi today are often too fast – no doubt in a hope to get more young people listening ie “sexing” up the music to coin a modern phrase. I played Beethoven, Mozart etc slower than was usually the way long before I heard of Wim Winters because the music made more sense to me when given time to breathe and make its affect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Robin Tranter. «… why are so many metronome markings impossibly fast…»

If the most important thing to you is that the music is played at slow tempos, I can do nothing for you. But if you want to get to know a different music historical truth than Wim Winters’ then I can contribute. So what do you choose?

LikeLike

»Wim Winters is the inventor…» No, he is not. It started with Erich Schwandt in 1974, when Wim Winters was two years old. Then came Talsma’s book in 1980. He believes that the slow movements should be played at the tempo we are used to today. Later, L. Gadient who believes that the slow movements should also be played at WBMP-tempos. It is Gadient’s variant that Wim Winters supports. Wim Winters channel AuthenticSound is only for the ignorant who are unable to expose his manipulations. Those who have knowledge, but who still support Wim Winters are musicians who do not care about the music in a historical context, but who prefer the music performed at a slow pace. I don’t know much compare to some others, but I still manage to find a number of errors in Wim Winters’ videos. This tells us about the channel’s weak academic level.

LikeLike

First off, I think Wim Winters is all but an amateur and I like his performances. Just like the performances of Bernhard Rüchti or others, for example. I do like slower performances and I hate the blurred haste of the so-called virtuoso which I compare to having a full Italian meal in 5 minutes: horrendous. But sometimes the slower performance become way too slow in WBMP. I understand that a “virtuoso” who spent the better part of his life practicing to become a whizz kid of the keyboard and makes a living out of it hates Wim Winters, as he is sort of pulling the rug from under their feet. At the same time I am able to fully appreciate the full texture of a musical piece only when played slower (and I frankly could not care less of the circus-like show-off of a virtuoso). Now, my personal take is that both parties of this dispute start from an unproven and unprovable assumption and that is: metronome markings are correct. Says who? Just because a guy called Beethoven or Czerny or Chopin wrote them? Could they not have made a mistake? So neither party is “right”. I think we need to go beyond the marking and play the music at a speed that allows us to communicate our feelings and others to capture them. Sure, there are Allegros, Andantes and Prestissimos. So what? My Andante might be a bit slower or a bit faster than someone else’s. But if it communicates and elicits the emotional answer in the listener that I want, then it is the right tempo. Markings or no markings.

LikeLike