Probably not. But out of the ones I’ve heard, I’ve enjoyed these the most.

Listen to the Spotify playlist

10. Te Deum: Prélude (Marc-Antoine Charpentier)

Featured on: Charpentier & Desmarest: Te Deum (Ensemble Les Surprises)

I considered choosing a less obvious track from this album, but let’s be honest, there’s a reason why this is such an evergreen. That rambunctious opening drumroll followed by those cock-a-hoop trumpets—there aren’t enough words in my thesaurus to describe my exhilaration whenever I hear this.

Nevertheless, I can heartily recommend the rest of the album as well. This recording shines from all angles like a Versailles chandelier. And then there’s the way the singers, doubtlessly for historical accuracy, Frenchify the Latin. So the ‘u’ in ‘laudamus’ doesn’t sound like ‘boot’ but like—well—‘parvenu’ (pronounced in French). Which, for some reason, I find endlessly entertaining.

9. Funeral March for Rikard Nordraak (Edvard Grieg)

Featured on: Grieg: Symphonic Dances (Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Edward Gardner)

On to more drums and winds, but less jolliness. This funeral march was written by a young Edvard Grieg to honor his friend and mentor Richard Nordraak, the composer of the Norwegian national anthem who died aged 23 of tuberculosis.

As dictated by convention, this march is a mixture of pomposity, tenderness, and grief. Although you might also detect a pang of guilt. After all, Grieg had ignored his sick friend’s incessant pleadings for a visit out of fear of catching the disease himself.

Towards the end of his life, Grieg always kept a copy of this score in his briefcase, in case there was need for some impromptu serenading when he suddenly dropped dead. It was played at his funeral in the end. If you want it to accompany your own interment, this recording by the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra will not disappoint.

8. Finale, Presto from Symphony nr. 98 (Joseph Haydn)

Featured on: Haydn 2032, Vol. 16: The Surprise (Il Giardino Armonico, Kammerorchester Basel, Giovanni Antonini)

I elaborately sang the praises of Haydn this year. So it makes sense to include some of his music in 2024’s overview. And the Haydn 2032 series is so good that I can include it in every year’s list.

This allegro is a perfect illustration of Haydn’s unique approach to composition. It starts with a lighthearted and, dare I say, forgettable melody. But then it branches out to all corners of the emotional spectrum.

The final surprise is a short but lively keyboard solo just when you thought the movement was grinding to a halt. At the premiere in London, this was played by the 60-year-old Haydn himself—never particularly known as a virtuoso. Imagine Bob Dylan suddenly turning into Billy Joel at the piano, and you’ll understand why the baffled crowd immediately demanded an encore.

7. A Ballet Through Mud (RZA)

Featured on: A Ballet Through Mud (Colorado Symphony)

Speaking of surprises, when I first heard this track in the background, my first guess was Rimsky-Korsakov—mainly because of the obvious quotation from Scheherazade. Turned out the composer was RZA, aka Robert Fitzgerald Diggs, of Wu-Tang Clan fame.

RZA is quite the renaissance man: rapper, filmmaker, actor, composer, and producer. It’s the producer job that brings in the C.R.E.A.M, though. So it’s no surprise that this album, apart from some beautiful melodies, stands out for its amazing orchestration.

6. At the Purchaser’s Option (Rhiannon Giddens)

Featured on: But Not My Soul: Price, Dvořák & Giddens (Ragazze Quartet)

Rarely is there such a heartbreaking story behind an innocuous title. Listen to Rhiannon Giddens tell it and stick around for her mesmerizing performance:

This original version gets its emotional punch from the combination of the laid-back banjo music with Giddens’ dignified and controlled anger.

The string quartet arrangement by Jacob Garchik is more extroverted, releasing all the pain and rage through plaintive countermelodies, plucking on snares, and hammering on wood. No substitute for the original, but certainly a worthy complement.

5. Tuba Mirum (Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart)

Featured on: Mozart: Requiem (Pygmalion, Raphaël Pichon)

This one will be on a lot of lists this year. Raphaël Pichon interweaves Mozart’s Requiem with lesser-known compositions by the composer that seem to eerily foreshadow his final work. Certainly interesting, but it’s the amazing performance of the pièce de résistance that will turn this into a classic recording.

In the liner notes, Pichon explains how Mozart’s Requiem is in some ways an extension of his operas, “[elevating] the orchestra to the status of an additional character, [even] the most complex character to convey what could not be expressed in words.”

That’s nowhere more evident than in the Tuba Mirum, an almost operatic quartet with a trombone as the fifth character. But Pichon also brings out the dramatic power of Mozart’s (or is it Süssmayr’s?) string section as a sixth member of the conversation.

4. Strike the viol (Jakub Józef Orliński/Henry Purcell)

Featured on: #LetsBaRock (Jakub Józef Orliński, Aleksander Debicz)

Let me get one thing off my chest first.

Dear classical music marketing people, I know pop-classical crossover is hard to sell. But let me assure you that album titles such as these only make things worse. It sounds like something that was coined in the seventies.

But wait a minute, I retract my words. I see you’ve added a contemporary touch: the completely meaningless hashtag! An unmistakable sign that you are truly ‘with it’.

Why should I care? Because this is a great album, and it would be a pity if the already tiny potential audience for this sort of thing was put off by this horrible title.

Countertenor Orliński and pianist Debicz bring cover versions of lesser-known baroque tunes and some of their own compositions in various 20th and 21st-century musical garments—ranging from jazz to hip-hop.

The combination of rich stylistic variety and consistent bare-boned instrumentation (mostly just voice, piano, drums, and bass) works extremely well. Just play this track, repress your purist prejudices (in either direction). And admit that it just, well, rocks.

3. Piano Quintet in G Minor: Largo (Sergey Taneyev)

Featured on: Taneyev: Violin Sonata in A Minor & Piano Quintet in G Minor, Op. 30 (Spectrum Concerts Berlin)

“Unfortunately for Sergei Taneyev, his music has long been held in high respect.” Nothing can be improved about that introduction by Gavin Dixon to this relatively unknown Russian composer. As a pupil of Tchaikovsky and teacher of Scriabin and Rachmaninov, Taneyev is a key figure in the history of Russian music. But he himself was more attracted to the Germanic tradition, earning him the nickname of ‘Russian Brahms’.

Much like Brahms, Taneyev combines strict compositional procedures with soaring expressions of emotion. This largo from his piano quintet is a nice example. It’s written in the respectable baroque form of a passacaglia, where one melody (presented very dramatically in unison at the beginning) is repeated throughout the movement. It’s a strong anchor for a deep dive into the innermost depths of the human soul—classical romanticism at its best.

This passionate aspect of Taneyev’s music seems to be overshadowed by his reputation as an academic traditionalist. His uneventful personal life might also have something to do with it. A lifelong bachelor, the closest he came to scandal was when Tolstoy’s wife took a shine to him. She wasn’t particularly subtle about it, which enraged Tolstoy. Nevertheless, the whole thing completely passed by Taneyev’s notice.

Maybe all that emotional torment in his music had no basis in real life. Or maybe his ‘lifelong friendship’ with Tchaikovsky was more complicated than most bios would have us believe. In that case, I hope someone discreetly informed poor Mrs. Tolstoy.

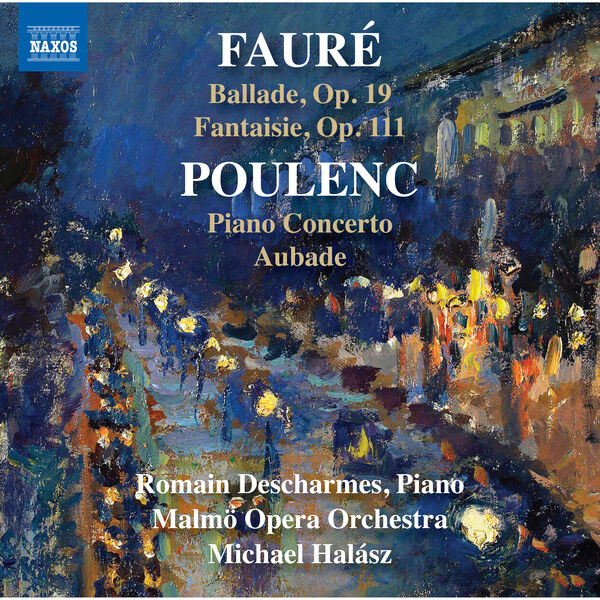

2. Piano Concerto in C-sharp Minor: Allegretto (Francis Poulenc)

Featured on: Fauré & Poulenc: Works for Piano & Orchestra (Romain Descharmes, Malmö Opera Orchestra, Michael Halász)

“Half monk and half naughty boy.” Now that’s more like it. It’s how critic Claude Rostand described Francis Poulenc, a composer who’s often derided for not being sufficiently serious. Understandable, when you listen to this first movement of his piano concerto, where he even outdoes Haydn in his constant thwarting of our expectations.

Maybe it’s a bit much and the whole thing misses a sense of unity. But his gorgeous melodies are unsurpassed by anyone but Mozart or Schubert. I couldn’t get the main theme out of my head for at least a week.

And then there’s that solemn brass chorale around the 6-minute mark, dialoguing with the piano and strings. Poulenc lets the seductive main theme kick in again with scarcely any transition, bringing the monk and the naughty boy face to face and creating a moment of sublime beauty.

1. Violin Concerto, Op. 15: II and III (Benjamin Britten)

Featured on: Britten: Violin Concerto, Chamber Works (Isabelle Faust, Symphonieorchester Des Bayerischen Rundfunks)

In 1939, Benjamin Britten arrived in the United States seeking refuge from the rise of fascism and militarism in Europe. His subsequently written violin concerto is therefore often regarded as a commentary on those troubled times.

Some say the young Britten went a little overboard with this concerto. The orchestra (especially the percussion section) is unusually large, and the violin part extremely demanding. It’s hard to imagine how some of the parts of the cadenza at the end of Part II can be played without at least one extra hand.

It’s impossible to separate these two movements: there’s no break between them and the theme of the passacaglia of Part III (a simple rising and then descending scale) is foreshadowed in Part II.

The general mood of Part II is one of terrible, beautiful violence (something that can only exist in art), reminiscent of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. There’s no triumph in Part III though, only resignation without acceptance.

It’s easy to imagine Britten writing this in 2024. But where would he escape to?