Are you one of those people who gets upset when Radiohead doesn’t play Creep? First of all: get over it. Second of all: take comfort in the fact that Radiohead is part of a respectable tradition of composers who despised their most beloved compositions.

Saint-Saëns hated Le Carnaval des Animaux, Ravel hated Boléro, Tchaikovsky hated the 1812 Overture, Beethoven hated Wellingtons Sieg, …

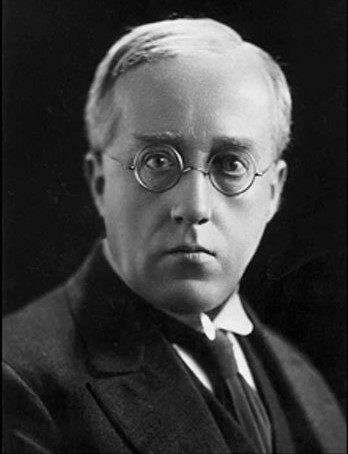

And Gustav Holst (1874-1934) hated The Planets.

The Planets: an unlikely success

The fact that The Planets was despised by its composer is strange in two ways:

- The Planets is the only composition for which Holst is widely remembered.

- Unlike the 1812 Overture or Wellingtons Sieg, The Planets is not a god-awful piece of classical music.

Holst’s orchestral suite is anything but a cheap crowd pleaser. Its musical forms are unusual, its time signatures often irregular and its instrumental combinations unorthodox.

In fact, during the first performances of The Planets, a few of the seven movements of the suite were always omitted. The idea was that the public wouldn’t be able to handle the full fifty minutes of such challenging music.

So why was the composer of The Planets later ashamed of it?

“The Planets seems to lift you up and transport you to exciting new worlds that are – at the same time – strangely familiar.”

Holst: composer in times of war

Holst wrote The Planets between 1914 and 1916 – the first two years of the Great War. You would think that such an Armageddon would have influenced his composition, but Holst always denied that. His main inspiration did come from Germany, but it was a purely musical one.

A few years before WOI, the musical world was already in turmoil. Critics and public waged fierce battles over compositions that broke with musical laws that had held up for centuries. Suddenly, listeners were deprived of:

- melodies they could sing along to

- rhythms they could dance or clap to

- harmonies that helped them to make sense of it all

In 1909, Schoenberg launched his Fünf Orchesterstücke, one of the first great examples of atonal music. Holst heard it, enjoyed it and bought the score. He liked it so much that he would name one of his next compositions Seven Pieces for Large Orchestra. Only later did he change the name of his suite to … The Planets.

Another ‘scandalous’ composition that influenced The Planets – just listen to the thumping irregular rhythms in Mars, The Bringer of War – is Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du printemps, which dates from 1912.

“Who wants to be remembered for an artistic anachronism – no matter how successful?”

Delicious mix of old and new

Holst was obviously excited by all these musical innovations. But that did not make him an avant-garde composer. In The Planets, he blended all these progressive elements and poured a generous helping of late-romantic sauce over it.

Or did he write a late-romantic composition and liberally spiced it with avant-garde elements? It doesn’t matter: the result is a perfectly balanced and extremely satisfying piece of classical music.

It was also exactly what the public needed after the horrors of the war: a composition that was new and exciting but also familiar and accessible. And with its more than fifty instrumental parts and two three-part choruses, it perfectly fitted the British love for pomp and circumstance.

Composing The Planets launched Gustav Holst into eternal fame

The emerging record industry also jumped on the success of The Planets. Jupiter was already recorded in 1922. A complete recording – conducted by the composer himself – followed in 1926. You can listen to it here. For comparison: Le Sacre du printemps had to wait until 1928 and Schoenberg’s Fünf Orchesterstücke even longer.

And in 1983, the author of this charming article about “the new compact digital players and disks (known as CDs)”, hoped that very soon the record companies would put out something else than predictable warhorses such as the 1812 Overture, Wellingtons Sieg and … The Planets.

The Planets by Holst: artistic anachronism …

So that’s what The Planets had quickly become in the eyes of the public and critics: a warhorse of classical music in the late-romantic style. It’s a judgment that deeply offended its composer. After all, who wants to be remembered for an artistic anachronism – no matter how successful?

It’s also a judgment that’s very unfair, inspired by the idea that ‘popular’ equals ‘inferior’ and that the only acceptable version of music history is a straight evolutionary line.

… or unintentional essay in escapism?

When you listen to The Planets, it’s hard not to be impressed by the unique sonic universe created by its composer. Because of the massive orchestra involved, its sound is big and expansive. Yet thanks to of Holst’s incredible talent as an arranger, it’s also light and transparent.

The result is music that seems to lift you up and transport you to exciting new worlds that are – at the same time – strangely familiar. It offers you a temporary escape from everyday life.

And that was not lost on an industry that specializes in such flights from reality.

The Planet’s satellites: from Death Star to Middle-earth

In case you were wondering, The Planets isn’t about space travel. Its inspiration is astrological rather than astronomical: Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune are character studies, not descriptions of big rocks in space.

George Lucas did not know that. Or, he didn’t care. Compiling the soundtrack for his Star Wars movies, he gave The Planets a spin. He particularly liked this fragment from Mars as the leitmotif for his main villain:

But he had no intention to pay any money to Holst’s descendants. So he asked composer John Williams to write something similar:

And John Williams wasn’t the only film composer inspired by Holst’s masterpiece. Echoes of The Planets also pop up in Braveheart and Battlestar Galactica.

And can you listen to this fragment from Jupiter without Middle-earth popping into your mind?

What would Holst himself have thought about all these bastard offspring versions of The Planets? Not much, probably. Though it’s safe to say it wasn’t the way he envisioned his legacy – if he had any vision of that at all.

But, as an almost contemporary of Holst – whose work suffered a similar fate – wrote: “Even the very wise cannot see all ends.”

Want to keep up with my classical musings? Enter your email address and click subscribe.

More about 20th century music

- Copland’s Appalachian Spring

- Review: Víkingur Ólafsson’s Debussy – Rameau

- Are these the best classical albums of 2020?

- Dag Wirén’s string quartets

Want to keep up with my classical musings? Scroll down, enter your email address and click subscribe.

Pingback: Review: Dag Wirén String Quartets | Classical Musings

Pingback: Appalachian Spring by Aaron Copland | Classical Musings